his bitter truth

an insight

[Continuing my reflection on Robert Caro’s The Power Broker]

In his early career, Robert Moses assumed that good ideas would speak for themselves. He believed that if a plan was well-reasoned and aimed at improving the city, it should naturally move forward. Instead, Moses found himself dismissed or pushed out of several roles, mostly because he underestimated how much politics shaped what could actually be done.

Robert Caro captures this gap between logic and reality:

Convinced he was right, he had refused to soil the white suit of idealism with compromise. He had really believed that if his system was right — scientific, logical, fair — and if it got a hearing, the system would be adopted.

But Moses had failed in his calculations to give certain factors due weight. He had not sufficiently taken into account greed. He had not sufficiently taken into account self-interest. And, most of all, he had not sufficiently taken into account the need for power.

Over time, Moses began to see that ideals weren’t enough on their own. To have any real influence, he needed a degree of power, and he needed to understand how decisions were made within the systems he hoped to change.

Belle Moskowitz, a trusted advisor to Governor Al Smith, played a significant role in that shift. She introduced him to the practical side of government: how to build support, how to negotiate, and where compromise was not a setback but simply part of moving an idea forward. Moses didn’t immediately abandon his principles, but he did learn to adapt them so they had a chance of becoming a reality.

The contrast between his and Belle’s approaches was apparent to those around them:

There was a real divergence of opinion there,” staffers recall. “Moses was very theoretical, always wanting to do exactly what was right, trying to make things perfect, unwilling to compromise. She [Belle Moskowitz] was more practical; she wanted to do the same things as Moses, but she wanted to concentrate on what was possible and not jeopardize the attaining of those things by stirring up trouble in other areas.

Moses then wasn’t afraid to admit, at least to himself, that his earlier convictions had limits:

He had always scorned the considerations of “practical” politics. Practical politicians had crushed and destroyed his dreams and had come near to crushing and destroying him. They had done it with an ease that added humiliation to defeat. And now, given a chance to learn their methods, Bob Moses seemed almost enthusiastic about embracing them.

This early period is easy to overlook compared to everything that came later, but it’s where Moses learned the basic truth that shaped his career: impact requires more than intention. It requires understanding the structure around you, and adjusting just enough to work within it.

new resource

Restorative Cities argues that many of the mental health challenges of city life (noise, crowding, pollution, long commutes, lack of daylight…) are not inevitable but rather failures of design. Written by Layla McCay, a psychiatrist and public-health specialist, and Jenny Roe, an environmental psychologist with architectural design experience, the book makes a strong case for putting mental well-being at the center of urban design.

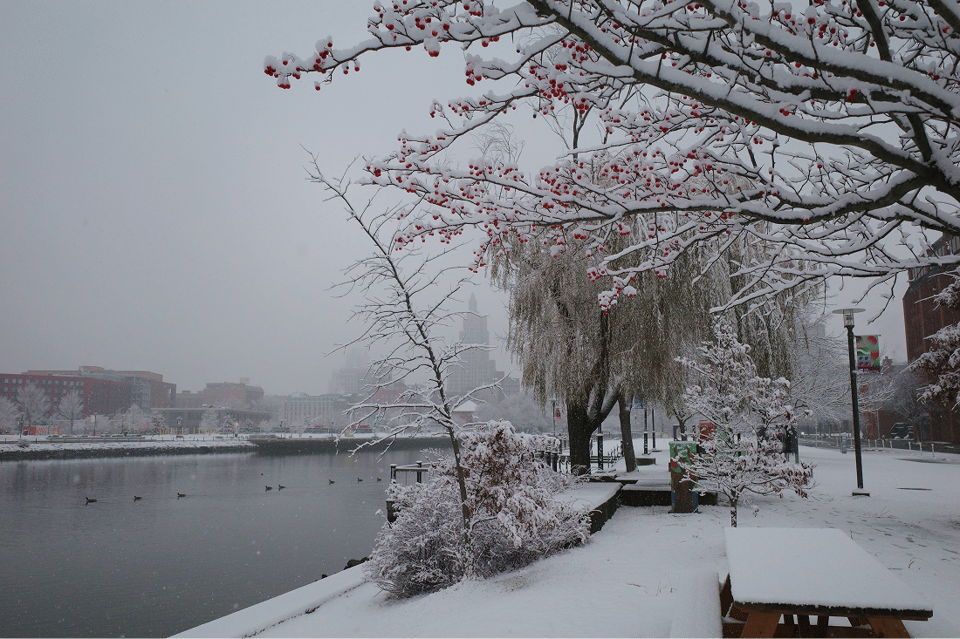

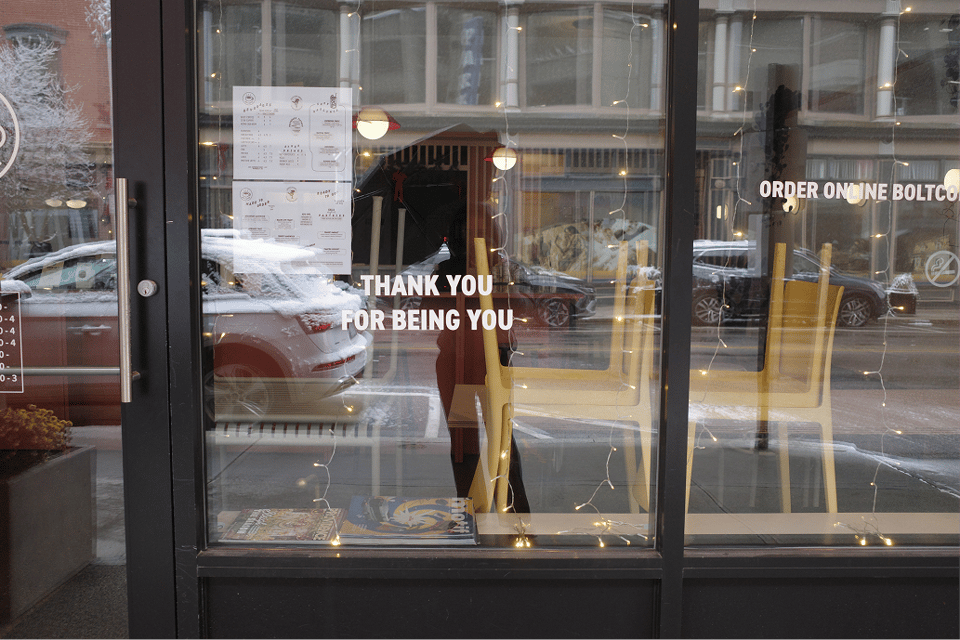

snapshots

if this resonates, you can receive new writing by email: