distances are shorter than they appear

an insight

When you look at a map of most American cities, it’s easy to underestimate how long it will take to get from one place to another. Distances appear short, but the reality on foot is different: long blocks, wide roads, and few much-needed interruptions — places that invite you to pause or simply keep your eye entertained.

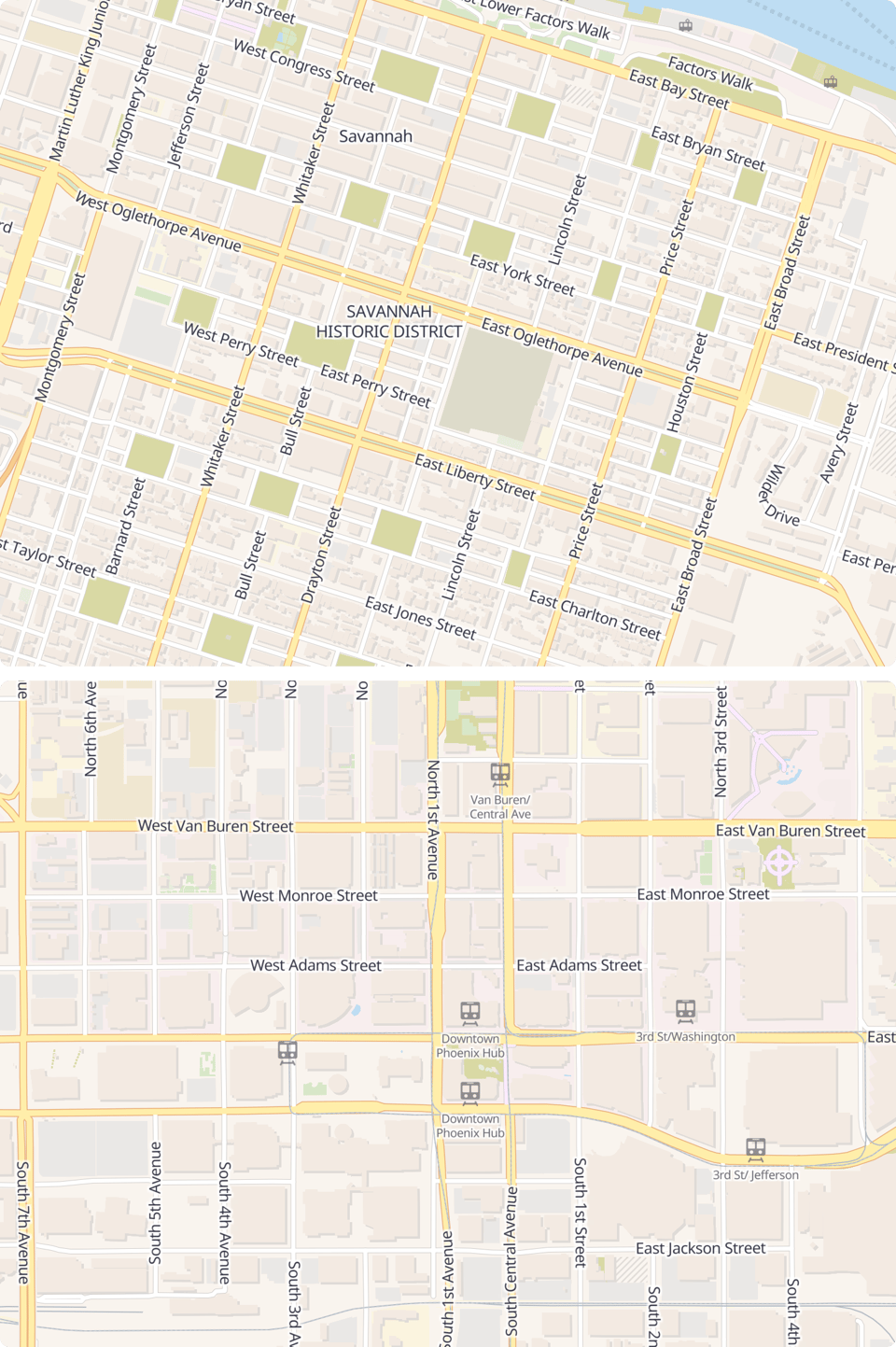

Savannah is a rare exception. For comparison, here are maps of Savannah and Phoenix at the same scale:

What’s striking is that Savannah was most likely not planned with “walkability” as we define it today. The original ward-and-square plan was pragmatic and orderly, designed for governance, defense, and incremental growth. Walkability emerged as a remarkably successful byproduct.

The repeating pattern of small blocks and public squares does something subtle. On paper, it might look monotonous (bring the winding medieval streets back!). On the ground, it’s the opposite. Just enough repetition makes the city easy to read and hard to get lost in, while small variations in buildings, streets, and squares keep each walk distinct.

Allan Jacobs points to Savannah in Great Streets as a near-perfect example of how urban form alone can shape livable streets. Short blocks, frequent choices to turn, and regular interruptions create a rhythm that supports walking without demanding attention. That matches my experience exactly: it’s easy to walk longer than planned, without noticing the time passing, without boredom, without needing a destination to justify the walk.

new resource

As alluded to above, I visited Savannah over the Christmas break, which of course led to a new city guide.

The guide includes a hotel housed in a former bank, a landmark in its own right, along with coffee shops and galleries that punctuate those longer-than-planned walks. I also added two walking routes: a classic one that stays mostly downtown, and an exploratory one that stretches beyond the postcard version of the city.

snapshots

A few bonus snapshots that didn’t make it into the guide.

if this resonates, you can receive new writing by email: